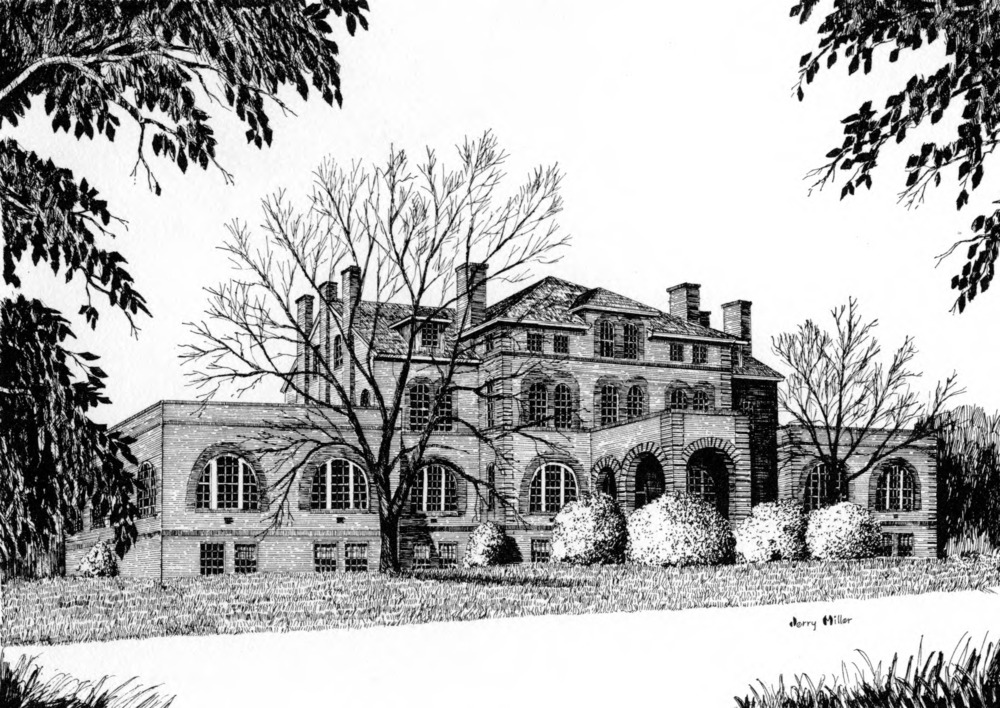

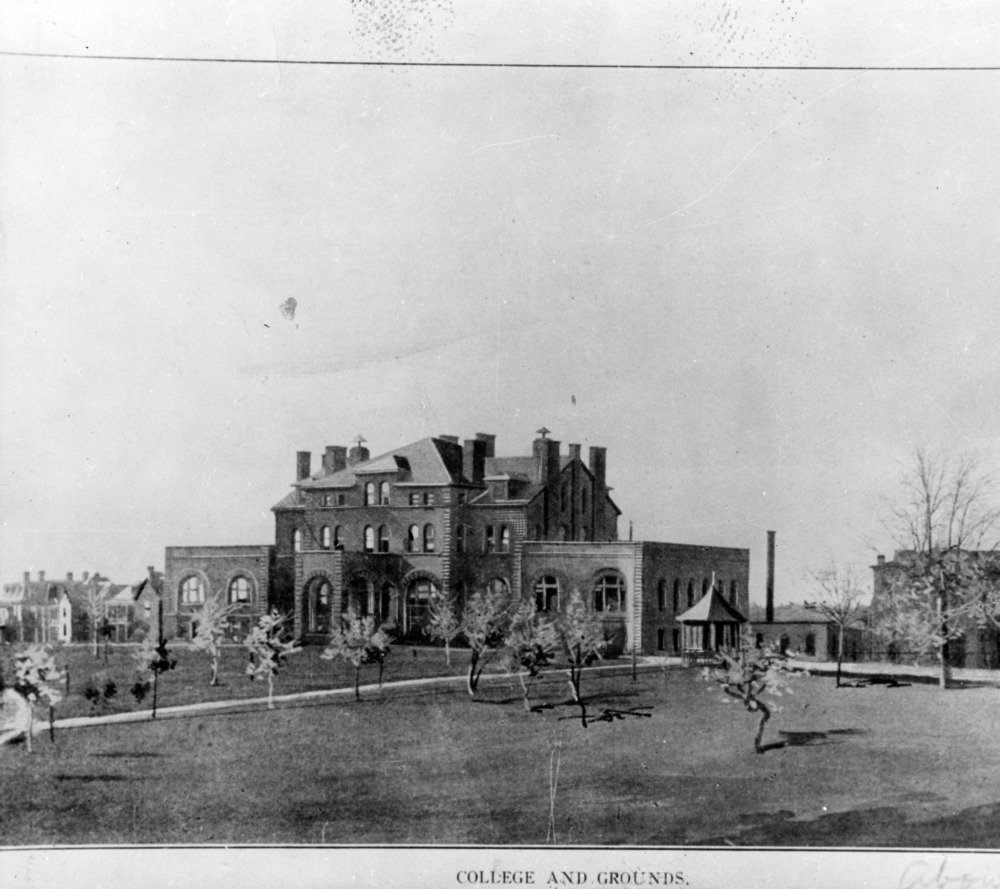

Holladay Hall at North Carolina State University, 1889 illustrated postcard

In a previous post on “Hidden Histories,” we discussed the School of Forestry’s (now College of Natural Resources) prisoner of war labor contract through the federal compulsory work program in 1945. The history of incarcerated labor on campus, however, goes back further than 1945. Historical records indicate that labor and supplies to build the earliest campus buildings was sourced from the State Penitentiary, or the Central Prison, located in close proximity to the university still today.

On March 3, 1887, the North Carolina College of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts was established using a combination of scrip funds reallocated from the University of North Carolina and funds from the Hatch Act of 1886, which funded the North Carolina Agricultural Experiment Station. The College Board of Trustees met for the first time in April 1887, and discussions began regarding the construction of a main building for the newly established college.

In 1887, the Board of Trustees appealed to the state legislature to provide support and resources for campus construction. In response to State College’s request, the NC General Assembly passed a law in the 1887 legislative session. As codified in Section 5 of Chapter 410, the directors of the State Penitentiary were required to furnish all brick and stone required to build the necessary buildings of the land grant college [NC State], to furnish convict labor for construction of said buildings, and for other purposes in connection with establishing the college. Labor and materials were provided free of charge to the college as long as that the work did not interfere with prison labor contracts or the general functioning of the penitentiary.

![Laws and resolutions of the State of North Carolina, passed by the General Assembly at its session [1887]](/sites/default/files/inline-images/pubs_edp_lawsandresolutions1887-0758.jpg)

The State Penitentiary’s biennial report from 1887-1888 states that the prison “furnished three-fourths of a million of merchantable brick to the Agricultural and Mechanical College.” The costs paid for labor and materials by the State Prison for construction of the college was $318.75 in 1887 and $5659.80 for 1888. On November, 9, 1887, the meeting minutes from the A&M College Executive Committee reported that the bricks would soon be ready to use, as “it has been determined that the brick should be hauled from the Penitentiary this winter.” Since the State Penitentiary had a brickyard on its grounds, it is likely that incarcerated people produced the bricks at the penitentiary and transported the bricks to the college for construction.

Construction on the college’s Main Building, now Holladay Hall, was completed in 1889. The Main Building was the first building on campus and, for years, contained virtually the entire college. People incarcerated at the State Penitentiary produced bricks from 1887 to 1888 that were used for the construction of the Main Building, as well as surrounding brick pathways and buildings on main campus. According to the 1892 college catalog, “The present building is of North Carolina brick, made and donated by the State Penitentiary by the direction of the Legislature of 1887.”

An Act of the NC General Assembly on March 11, 1889, significantly changed the financial relationship between A&M College and the State Penitentiary, as the State Penitentiary was now authorized to charge the college for labor and materials provided. Prison and college records from 1895, 1902, and 1909-1910 indicate that the State Penitentiary was charging the college for the cost of bricks, which were likely used to build additional campus buildings and spaces in the following years. In 1894, it was also reported that the incarcerated people at the State Penitentiary “have done the laundering for more than one hundred students of the A. and M. College.”

![Reports of the superintendent, warden and other officials of the state's prison, Raleigh, N.C. [1909/1910]](/sites/default/files/inline-images/pubs_serial_prison_reportssuperintendent1909-026.jpg)

The State Archives of North Carolina holds “registers of prisoners” from 1870 to 1955, but these registers do not clarify which people were assigned to work on various labor projects while incarcerated at the State Penitentiary. From the 1880 to 1890 prison registers, we can discern that the large majority of incarcerated people at the State Penitentiary were African American men, described in the registers as “negro” or “mulatto.” Furthermore, the registers held at the State Archives of NC indicate that some of these incarcerated people were charged with several years of imprisonment for petty crimes, and a number of people were incarcerated multiple times during their lives.

In Twice the work of free labor, Alexander Lichtenstein argues that convict labor was an exploitative process by which predominantly African American men and women were conscripted to provide unpaid labor while incarcerated, often in terrible and dangerous conditions, in the American South after the Civil War. While archival records offer glimpses into the lives of incarcerated laborers, significant gaps persist in documenting their lived experiences and the enduring legacies of their exploitation in the prison system.

For more information about campus buildings and their histories, refer to the Brick Layers Project. If you have any questions or are interested in viewing Special Collections materials, please contact us at library_specialcollections@ncsu.edu or submit a request online.

The Special Collections Research Center is open by appointment only. Appointments are available Monday–Friday, 9am–6pm and Saturday, 1pm–5pm. Requests for a Saturday appointment must be received no later than Tuesday of the same week.

“Brick Layers: An Atlas of New Perspectives on NC State’s Campus History.” Brick Layers, May 23, 2021. https://bricklayers.history.ncsu.edu/.

Browne, Jaron. “Rooted in Slavery: Prison Labor Exploitation.” Race, Poverty & the Environment 14, no. 1 (2007): 42–44. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41555136.

LeFlouria, Talitha L. Chained in silence: Black women and convict labor in the New South. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2016.

Lichtenstein, Alexander C. Twice the work of free labor: The political economy of convict labor in the New South. London: Verso, 1996.

Smith, Lisa D., and Jo White Linn. “Central Prison.” NCpedia, January 2006. https://www.ncpedia.org/central-prison.