The man who let the light in

As architect Phil Freelon’s archives come to the Libraries, a brilliant legacy is preserved

When you walk across the Brickyard toward the D. H. Hill Library, you instantly feel how special it is. Students rush to classes across its red and white bricks or sit on the low wall to eat lunch or check their phones. Barkers for campus organizations offer cookies or donuts for donations. You can even get fresh kale if it’s a farmer’s market day.

It’s hard to imagine the university without its cherished public square. But while he was a student here, the renowned architect Phil Freelon had an idea to make the Brickyard even more special.

“I designed an underground chapel for the little piece of land that sticks out into the Brickyard,” Freelon says, reminiscing about student projects from the 1970s. “It had these solar collectors that brought all the light down. It was kind of cool. That piece of land is still there, that little green area just in front of D. H. Hill.”

Letting sunlight come into buildings is a hallmark of Freelon’s designs for libraries, museums, academic buildings, and cultural centers all over the Triangle and the country. Whether filtered through the grand, iron corona around the new Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture on Washington D.C.’s National Mall, or through the humble slats around the cozy Lake Johnson boathouse in Raleigh, light’s presence in Freelon’s buildings signals openness and welcome to all.

Freelon is focusing some of that light on the NCSU Libraries by choosing our Special Collections Research Center as the home for his architectural archive. Over the last two years, he has donated many architectural records, drawings, and models from his earliest years as a practitioner and will gradually add to his archive in the future.

“I’m especially glad that the Libraries took the design awards because we were running out of space here,” Freelon laughs, sitting in a pool of afternoon sunlight in a meeting room in his firm’s Research Triangle Park offices. “There were lots of awards from the American Institute of Architects, from the local to the national levels. All those certificates are at the Libraries now, so I’m happy that they’re in one place and safe and protected.”

Read through those awards and you’ll find yourself listing some of the most significant museums and cultural institutions in the country, including the Harvey B. Gantt Center for African-American Arts and Culture in Charlotte, the Museum of the African Diaspora in San Francisco, the National Center for Civil and Human Rights in Atlanta, and the Reginald F. Lewis Museum of Maryland African-American History and Culture in Baltimore.

You’ll also recognize the names of buildings all over the Triangle area: the Durham Bulls Athletic Park, Durham’s Hillside High School and Hope Valley Elementary School, Raleigh’s Lake Johnson Boathouse, the LORD Corporation’s world headquarters in Cary, and the parking deck at the Raleigh-Durham International Airport. It’s hard to live in the Triangle without having walked into at least one Freelon building.

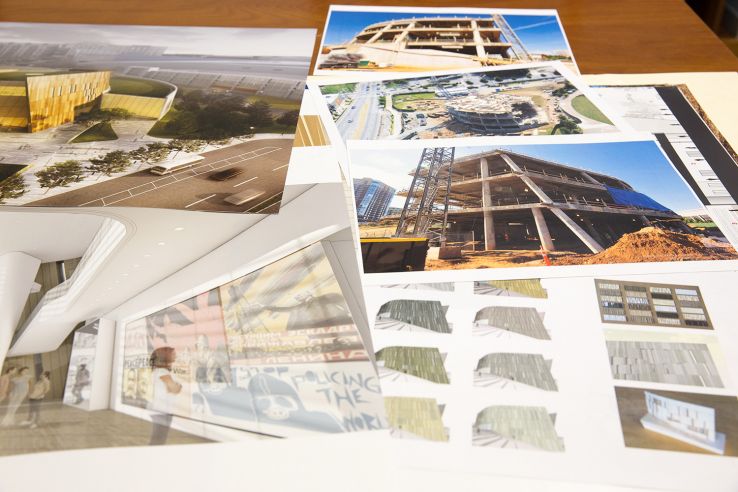

Freelon has even designed several buildings on NC State’s campus, including the Partners III Lab Building on Centennial Campus and the new Gregg Museum of Art and Design addition, currently under construction and due to open later this year.

“It means a lot to have my archive at the Libraries, because I’m very proud of being an NC State alumnus,” Freelon says. “And also I’m thankful to NC State for the training I got there at the College of Design, as well as the opportunity to teach. They opened up my mind in so many different ways.”

Freelon grew up in an art-infused household in Philadelphia. His parents took him to performances and museums, and he remembers visiting his grandfather’s painting studio with fondness. Pencils and brushes found their way into his hands very early on. In high school he gravitated toward design and technical drawing and began to get a sense of what architecture was.

The arts remain a large part of Freelon’s life today. Appointed in 2011 by President Barack Obama to the U.S. Commission of Fine Arts, he is an accomplished photographer and occasionally juries exhibitions such as the Bull City Sculpture Show, which placed 12 large outdoor works around downtown Durham in 2014. His wife is the Grammy-nominated singer and composer Nnenna Freelon, and two of their three children are accomplished artists currently involved in the Afrofuturist hub Blackspace in Durham.

Freelon’s college years didn’t begin at NC State. After his sophomore year at Hampton University, he was recruited here—for architecture, not athletics.

“I excelled at Hampton,” he says, “and one of my professors, actually the head of the department, had a network of other colleagues around the country because he was on the accrediting team for various schools. He said, ‘You should look at these other places, you should probably move on.’ It was a really generous thing for him to do.”

Freelon visited Raleigh over the summer and met then-Dean Claude McKinney and architect Roger Clark. They persuaded him to transfer to NC State. “I was flattered that they would go out of their way to call my home and encourage me,” Freelon recalls. “They really kept after me.”

Thus began a lifelong relationship with the university. In addition to being a student in the College of Design in the 1970s, Freelon has taught at the College, served on its Design Guild/Design Life Board, the Board of Visitors, and the Board of Trustees. But those first couple of years were challenging.

“I still had to unlearn a lot when I went to school,” Freelon says. “At the College of Design they have to reorient your mind about how your creativity can be used in the built environment. I didn’t really know what architecture was about. It was more of a notion of what you see on television. I’d never been in an architecture office until I got to college. So when I got to architecture school here, it turned out to be everything I’d imagined and more.”

Freelon still remembers every student project clearly: his subterranean chapel, studio spaces, multi-family housing, a new building for the North Carolina Museum of Art. He won the student award from the faculty here before moving on to get his Master of Architecture degree from MIT. He then received a Loeb Fellowship and spent a year of independent study at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design.

Freelon still remembers every student project clearly: his subterranean chapel, studio spaces, multi-family housing, a new building for the North Carolina Museum of Art. He won the student award from the faculty here before moving on to get his Master of Architecture degree from MIT. He then received a Loeb Fellowship and spent a year of independent study at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design.

In addition to his teaching at NC State, Freelon has been a visiting critic/lecturer at Harvard, MIT, the University of Maryland, Syracuse University, Auburn University, the University of Utah, the California College of the Arts, Kent State University, and the New Jersey Institute of Technology, among others. He is currently on the faculty at MIT’s School of Architecture and Planning.

Freelon founded his own firm, The Freelon Group, in 1990, focusing on higher education and science and technology spaces in addition to libraries, museums, and cultural centers. Freelon merged his 50-person firm with the global design and architecture firm Perkins+Will in 2014, and currently serves as the Managing Director and Design Director of its North Carolina office in RTP.

His upbringing and background have always shaped his firm’s work. “We don’t do everything. We kind of specialize in certain projects,” he says. “And when you do that, you develop some expertise.”

“We’re known for our library work, our museum work. When it comes to those sorts of clients, we listen very carefully and try to infuse some of the vision and mission of the institution into the architecture. The architecture can help to convey the story in the case of a museum. That’s the special approach that we bring.”

As a black architect, Freelon has built a reputation upon his particular ability to illuminate the visions of African American museums and cultural centers. The iron facade of the National Museum of African American Culture and History draws upon the idea of a crown in Yoruba art and architecture, and refers in its materials to the wrought-iron work done by black artisans—some slaves, some free men—in cities like Savannah and New Orleans.

The side of Charlotte’s Gantt Center recalls the external stairwells on a school building in the city’s predominantly black Brooklyn neighborhood, which was razed in the name of “urban renewal” in the 1960s. Nicknamed the “Jacob’s Ladder,” the stairwells have become a stylized, aspirational web covering the Center’s entire side, skinned with a patterned surface based upon quilt designs.

Freelon takes his place in the history of African American architects very seriously, acknowledging elders such as Paul Revere Williams and Julian Abele, who designed much of Duke University but wasn’t acknowledged for it until recently. While at NC State, Freelon published an article about Abele’s career and accomplishments in North Carolina Architect magazine.

“I knew about Abele long before most people. He’s inspiring,” Freelon says. “If you think about the time in our country where this African American did what he did, it’s just remarkable. So how can I even think about complaining about any situation when gentlemen like Julian Abele and Paul Revere Williams did so much at a time in this country when the oppression was very limiting and racial discrimination and all the other things we talk about today were there, only worse. And for this gentleman to be from Philadelphia, my hometown, there are all sorts of parallels.”

While Freelon looks back to his predecessors, he also nurtures and mentors future architects today—less than 2% of all registered architects in the country are black.

“Being who I am and having the visibility I have, people seek me out and want to know if I can give them advice and mentoring. Some of them I hire, and some of them I refer to other people,” he says. “I tell them that this has been a great career and to keep a positive attitude. As far as complaining about discrimination and so on, it’s good to be aware and to try and protect yourself and do the best you can, but you ought not to let it color your thinking about your work or discourage you.”

“Is it going to be smooth sailing all the time? No. Will there be challenges related to who you are and how you look? Sure. But if I had felt like that was going to be an impenetrable barrier, then I would have done something different.”

Removing barriers to let light in is a big part of Freelon’s architectural legacy over a career spanning five decades. That legacy has found the right home in the Special Collections Research Center at the NCSU Libraries.

“Being at NC State was a fascinating and productive period of my life that I’ll never forget,” he says. “I’m grateful for those experiences, and for developing the skills that allowed me to move on to the next level. That’s one of the reasons I said yes when the Libraries asked for my papers, because I have this deep affinity for NC State.”

Since the publication of this feature in 2017, the NCSU Libraries has changed its name to the NC State University Libraries and the D. H. Hill Library has been renamed to the D. H. Hill Jr. Library.