African-American Protests, Spring 1969 (Part 2)

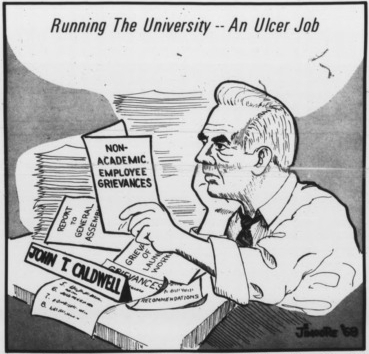

We continue our look at racial conditions at NC State 50 years ago during the spring of 1969, particularly protests of African-American employees and students. In the Special Collections News post of March 15, we left off with the convocation called by Chancellor John Caldwell, which followed demonstrations supporting changes in pay and working conditions of university custodial employees and during a time of unrest on college campuses in North Carolina and across the United States.

After the 5 March 1969 convocation at NC State, the university did make efforts to address some of the employees' issues. The university appointed Bobby F. Holloway as the first African American supervisor in the physical plant, and the Board of Trustees’ Executive committee sent the governor a recommendation for a 10% salary increase for non-academic employees. On March 21 the Technician student newspaper reported that custodial staff earned less than $4000 a year in 1969 (the annual average U.S. income that year was $ 5,893.76).

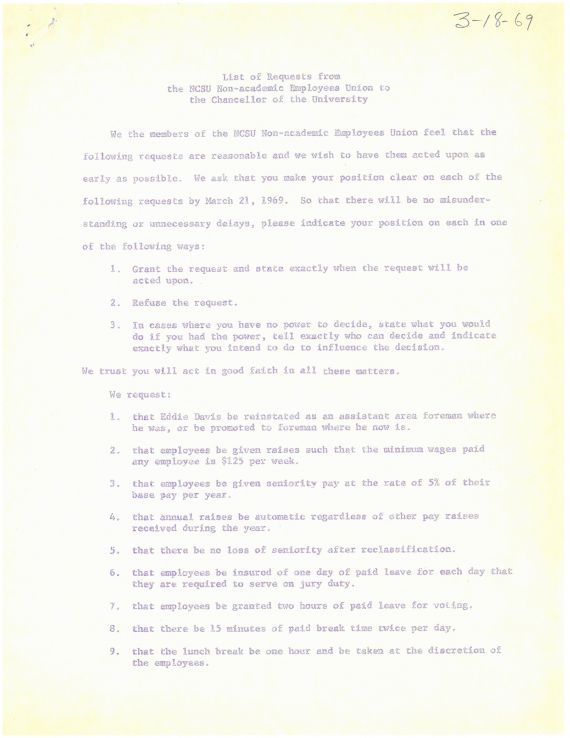

Employees' List of Requests

On March 18, the Non-Academic Employees Union (NAEU) Grievance Committee, chaired by Willa B. (or Willie Mae) Hinton, met with Chancellor Caldwell and presented a 43-point “list of requests” (the university called this the “43 grievances.”). At a press conference afterwards, physical plant employees indicated they "had been threatened and harassed for participating in demonstrations.” Spokesperson Eddie Davis had the understanding “that participation [in demonstrations] would constitute grounds for firing." He said the university threats had "been occurring for some time now," but he rallied his co-workers by saying "Brothers and Sisters, we are going to walk our way to better times."

The list of requests was wide ranging. It covered many bread-and-butter issues: pay (minimum of $125 per week), hours, breaks, overtime, paid leave, work hours, seniority, and job classifications. In it employees requested break rooms, preferential consideration for job openings, public posting of open jobs, and improvements in working conditions. In addition, they wanted the university to provide “free reserved parking spaces for employees near their work areas” and “free tuition and fees to all legal dependents of University employees.”

Within a week, Chancellor Caldwell issued a written response to each request, and he sent a copy to the non-academic employees. Some were upset, however, because he didn’t meet with them. Davis said, "I'd rather have someone tell me in person what was in the document than read it." (The first of the 43 requests asked for the reinstatement of Eddie Davis as assistant area foreman, but Caldwell indicated that would not happen until the case had been reviewed.) The chancellor’s responses indicated limitations in what he could do because state government oversaw many personnel issues. Some employees called this “buck-passing.”

On March 25, the university approved a solution to one grievance: “That no women be assigned to men's dormitories and that those women presently assigned be re-assigned to other buildings." Caldwell said, “We understand this request. The change has been initiated with full implementation expected within three weeks.” NEAU did not state why it requested the reassignments, but women custodians may have been harassed in all-male dormitories. Providing some insight into the women’s working conditions, the list of requests included “that no women be required to do heavy work such as stripping floors, operating buffers, or carrying heavy containers . . . . that no employees be required to clean undue filth caused by malicious actions of students . . . . that all employees be addressed with titles of respect such as Mr., Mrs. or Miss and that degrading terms like ‘boy’ and ‘girl’ not be used . . . . [and ] that the University place Black people in supervisory and managerial positions . . . especially . . . in areas where most of the employees are Black.”

Reversals and a Heated Exchange

Also on March 25, the situation became more complicated when laundry workers charged the university with “discriminatory and unfair management practices.” Seven employees met with the laundry manager, and they presented complaints about hours, pay, and lack of African American supervisors. Interestingly, they said that the NAEU did not represent them.

The next day the Non-Academic Employees Union and the Society of Afro-American Culture (SAAC) student group organized a rally attended by approximately 150 people. Davis addressed the crowd, as did SAAC’s Eric Moore and Jim Lee. Moore asked if the university was treating the employees as “human beings or machines,” and the audience applauded when Lee said African Americans were “sick and tired of being told how they're supposed to be.” There was general dissatisfaction with Chancellor Caldwell's responses to the 43 requests.

A few days later on March 28 the dispute took another turn after the university approved "in principle" changes to the custodial workday from 5:00 am - 1:30 pm. to 8:00 am – 5:00 pm. Then 178 janitors and maids apparently broke rank with their colleagues and issued a protest petition: "We the undersigned wish to go on record as protesting the disrupting of our present work conditions and schedules for the advantage of just a few individuals. We are very satisfied with our present assignments and do not want to change them." They also claimed to be represented by the Physical Plant Employee Association rather than the Non-Academic Employees Union (The former organization had existed since the 1950s, but it was not very active.)

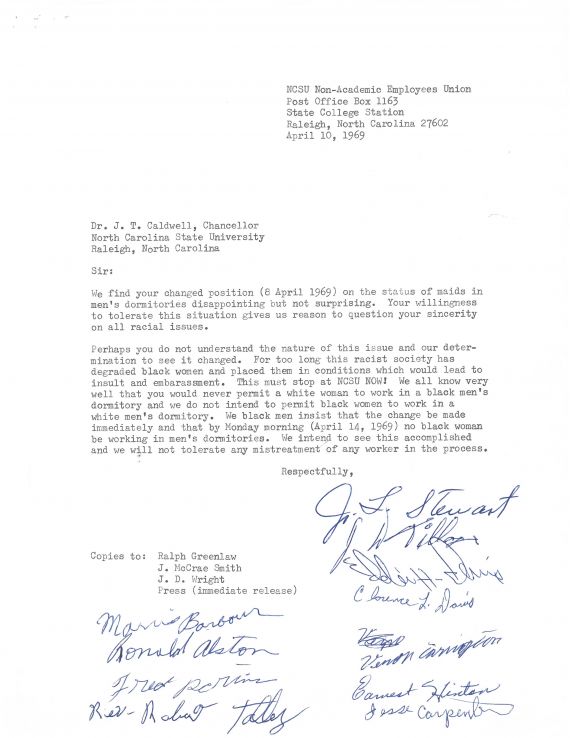

On April 8, Chancellor Caldwell sent a letter to non-academic personnel reversing his decision to reassign women employees from men’s dorms. He claimed the petition of the 178 janitors and maids was signed by a “large majority of women employees now assigned in men's dormitories' requesting that they not be transferred.” Another reason for the reversal was that the women working in the men’s dorms would have to be replaced with male employees, who would then need to work until 4:00 pm instead of their current 1:00 pm: “This would work a hardship on workers that now have extra afternoon jobs." The university would “reassign women from dormitory to other buildings as requested by individual women workers to the maximum extent that is possible to do so without violating the rights and desires of other employees."

Two days later, 11 male employees (including Eddie Davis) sent a strongly-worded letter to Caldwell: "We find your changed position on the status of maids in men's dormitories disappointing but not surprising. Your willingness to tolerate this situation gives us reason to question your sincerity on all racial issues." They continued: "For too long this racist society has degraded black women and places them in conditions which would lead to insult and embarassment [sic]. This must stop at NCSU now! We all know very well that you would never permit a white woman to work in a black men's dormitory and we do not intend to permit black women to work in a white men's dormitory."

The chancellor reacted to this as an ultimatum, and he wrote back, "You have chosen to send me a letter which in substance and spirit is unjustified, unreasonable and disrespectful. I cannot, therefore, honor it. You have apparently been misled. I suggest that you restore your thinking to a more helpful and useful position for all concerned.”

Sit-In and Demonstration

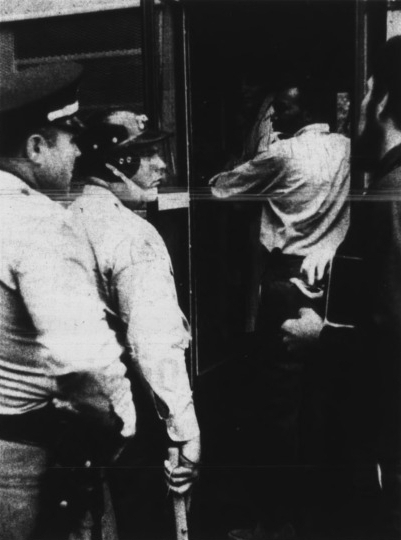

The following Monday, April 14, events moved quickly. Employees Willie Vines, Snodeen Perry, Catherine Howell, and Mildred Raines refused to work in the male dormitories, and their supervisor fired them at approximately 11:30 am. One hour later, 15 or 16 physical plant employees conducted a sit-in at the Office of the Chancellor. Included were Vines, Raines, and Perry, as well as Willie Hinton and Eddie Davis. They spoke with Chancellor Caldwell for some time. Campus police tried to make them leave, but they refused to go. Authorities then arrested them, took them to a Raleigh police station, booked them for trespassing, and then released them. That afternoon, African American students held a demonstration outside Holladay Hall.

In the evening a crowd (reports indicated anywhere from 75 to 150 people) gathered near the union and then walked to the Chancellor’s Residence (today’s Gregg Museum) where they protested, chanting and carrying torchlights. The group included students from Shaw University and St. Augustine University; perhaps they comprised the majority of people there. The Technician reported “several incidences between blacks and bystanders” and that an African American demonstrator assaulted an NC State student with a chain.

The following morning Caldwell met with the 4 women fired the day before, and they aired their grievances. He said that they would remain discharged, but "after a reasonable length of time, they might feel free to re-apply." Also that day the university fired Eddie Davis and James Dewey Smith. Davis was dismissed because of an unauthorized absence (he said he had been at a press conference held by NAEU). Smith was dismissed because of an unauthorized absence and because "he was participating in an action calculated to harass and embarrass the Chancellor of the University." (He had apparently left his job while on duty in order to attend the demonstration at the Chancellor’s Residence.) In addition, Smith was also accused of the student assault involving the chain. Other employees that had participated in the sit-in could return to work, but the university stated that continuation of their employment was under review.

Then late in the afternoon, Caldwell announced the discontinuation of custodial service in residence hall rooms. According to the chancellor, this "resulted from financial pressure brought by recent pay raises for employees and the employees request that African American maids be transferred from male residence halls. The chancellor indicated that "cleaning rooms would henceforth be the responsibility of the occupant," and he ended his statement by saying "I am happy to report that women workers, effective April 15, will no longer be assigned to men's residence halls."

Campus Reaction to Custodial Employees

During March-April 1969, campus support for and criticism of the employees played out in the Technician’s “Reader Opinion” column. It began on 19 March 1969, when a Technician editorial supporting the workers’ 43 requests stated, “Some will be bothered by the $125 per week minimum wage, as it will place custodians on a better wage level than many secretaries and other staff members.” It went on to ask, “So what's wrong with that? What is it in a housekeeping employee that makes him any less deserving of a comfortable life?”

The following week a “disgusted secretary” responded: “Well, I'll tell you what's wrong with it. In my years here I have never had my desk wiped off, and I have to polish my shoes every night because of the dust and dirt on the floor day after day. I am constantly catching the janitors asleep in the offices and also in one of our conference rooms. They should be doing a little 'housekeeping' instead of making demands that are not fully deserved." Later in the letter, she claimed "I could do a housekeepers' job but he or she most likely could not hold down a secretarial job. In all fairness to employees of the university, we are paid according to our abilities and I would hate to think that I have had college and business school training only to end up making less than a housekeeper just because he thinks he should live on my level. If they want to earn more money let them train for it and then live on the same level as a secretary."

A week later “Disgusted Secretary No. 2” echoed the first by claiming the floor in her office hadn’t been cleaned in two years, the office bathroom in two months. She concluded “I challenge the Technician to take a survey of how others, STAFF and students, feel toward the work these workers are producing (?). Only then can the full picture be seen and justice to all 'without regard to race, creed, or national origin . . . ' and all that other bull%$+&*!"

This resulted in a letter from “Maid No. 1 and 55 others”: “When that survey has been taken, we maids suggest that the Technician take another survey of how others, maids and janitors and students feel toward the work the secretaries are producing (?), for no white person is so white that he is invisible during day time. How does the secretary think we feel when we see her standing in the halls talking, down in the restrooms talking, in the lounges on coffeebreaks (that we don't get) talking, personal calls on telephone, late coming, early leaving. We see this and we know she is paid twice as much for her 40 hours as we are paid for our 40 hours, and she has all the benefits (privileges) that we are seeking."

Letters came in supporting the custodial staff. On March 28 the Technician published one from a sociology junior who supported higher pay for the employees, although not an increase in student tuition and fees to cover it. On April 11, the newspaper printed a letter from N. White Connor, assistant dean for research, who said about Daniels Hall, “The maid assinged [sic] to this area should be commended for her efforts. She is extremely conscientious and she does a truly outstanding job in every respect.” Psychology Dept. secretary Ann L. Sterling took a different approach when she said that the “disgusted secretaries” missed the point: “that secretaries although making about twice as much as maids and janitors are also exploited and underpaid." She earned $85 per week, “not what can be called a ‘living wage,’” so the $40-45 per week of the custodial staff was “a bare subsistence wage” that lacked that the benefits of paid vacation, sick leave, etc. that she received. “It would seem to me,” she concluded, “that instead of trying to keep the maids and janitors on a low wage scale, it would be better all around if the secretaries were to make common cause with the NAEU (Non-Academic Employees Union); work with them; and ask that ALL non-academic workers, including secretaries, be given a 'living wage.'”

In June, we will continue our series of articles on African Americans at NC State in 1969.

(Part 3 of this series on African Americans at NC State in 1969 was posted on 11 June 2019.)

Addendum, 5 June 2019

Further research has revealed that on 23 April 1969, the Technician’s Mary Porterfield reported on interviews she conducted with some of the facilities employees, who indicated they were dismissed for reasons other than those stated by the university, which were for “neglect” and “refusal to work.” Eddie Davis claimed he was fired for “having held a press conference [for the union] on unalloted time.” Porterfield added “Davis feels that it is his duty as chairman of the grievance committee to hold such conferences after any significant meeting concerning the worker and plant.” (A separate article in the newspaper quoted Physical Plant Director J. McCree Smith as saying about Davis, “he was fired because of his leaving his job without telling any one when he was coming back. He had been doing this before. This was unauthorized leave. He was doing it without restraint.”) The Technician reporter also interviewed 2 of the 4 custodians that were fired. The women said they tried to act on the chancellor's statement that they could request reassignment from working in men’s residence halls, but they were subsequently told by facilities management that it “would not be possible because of the lack of vacancies” in other buildings. The women thereupon refused their existing assignment.

In addition to the Technician articles linked above, some archival sources have been consulted for this post. “Recapitulation of Recent Events, the Non-Academic Employees Union” (1969) is a compilation of documents created by university physical plant administration concerning the employees, their requests, the protests, and university actions. It can be found in the Facilities Division Design and Construction Services Department Records (UA 003.004, Box 136, Folders 3-4). In addition, petitions and the list of requests, with the employees’ original signatures, can be found in the Office of the Chancellor Records (UA 002.001.004, Box 84, Folder 13). To access these documents please contact the Special Collections Research Center.