What does your genetic future look like?

In an exhibition at the Libraries, the Gregg Museum, and the NC Museum of Art, artists use the lens of biotech to envision humanity’s futures.

Mice in the library, a corn maze, and a visit from legendary author Margaret Atwood—it’s been an unforgettable year for exhibits at the Libraries!

In its most ambitious and expansive exhibits project to date, the Libraries partnered with NC State’s Genetic Engineering and Society Center (GES) and independent guest curator Hannah Star Rogers to organize Art’s Work in the Age of Biotechnology: Shaping Our Genetic Futures. The exhibition and its dynamic programming brought genetic engineering and biotechnologies out of the lab and into public places and discussed their consequences through the lens of art and design.

The visually stunning and thought-provoking exhibition showed at the Gregg Museum of Art & Design and in the physical and digital exhibits spaces in the Hill and Hunt Libraries, and included the work of 22 artists from around the world in the emerging field of bioart. Art’s Work also included an interactive corn maze on the grounds of the North Carolina Museum of Art (NCMA) and attracted The Handmaid’s Tale author Margaret Atwood to campus for a day of events, featuring a sensational talk about the intersections of technology and humanity.

Biotech, as an ancient concept

The term “biotechnology” tends to conjure an image of white-coated lab technicians peering through microscopes at DNA. But human engagement with biotechnology has a long history. The earliest farmers were selectively planting crops to increase yields and breeding animals to produce desired characteristics—the ancient equivalent of modern biotech. These agricultural practices were captured in art in Popol Vuh creation stories and Mayan representations of farming.

Art’s Work extended this history into futures both speculative and real, through works that prompt new ways of thinking while emphasizing the historical context of biotechnological innovation, medical practice, and genomic science. By bringing art and modern biotechnology together, the exhibition reached toward new understandings about the human condition, our bodies, the environment, and the other species that share the planet.

Rogers, an independent curator and Visiting Scholar at the University of Edinburgh, took the lead in selecting artists for the exhibition and owned the vision for a show that would appeal to museum-goers, scientists, and the public alike. Rogers has also been past Director of Research and Collaboration for Emerge: Artists and Scientists Redesign the Future 2016, and she served as Guest Bioart Curator for 2017.

“The exhibition asks visitors to participate as witnesses, donors, or interlocutors in the nuanced conversations around genetics,” Rogers told the Art the Science blog in an interview. “NC State University is the perfect place to discuss these issues, as the institution has been at the forefront of not only discoveries and innovations in genetics, but is also the home of the GES.”

Rogers praised the exhibition’s partnership for the multidisciplinary expertise brought to bear in the multi-year process. “The GES Center’s co-director, entomologist Fred Gould, along with Molly Renda with the Libraries’ Exhibits program, had discussed creating an art exhibit that addressed the same ethical and practical questions being discussed among GES’s interdisciplinary scholars—including ecologists, social scientists, historians, philosophers, and anthropologists.”

Gould, a Distinguished Professor of Entomology and a National Academy of Sciences member, brought a hard-sciences perspective to the team. Renda’s extensive background in art and design complemented Rogers’ depth of knowledge about contemporary bioart.

“The Libraries was a natural fit with its record of engaging exhibits, its understanding of the research life cycle, and its access to subject specialists and new technologies,” Rogers continued. “This unique team made it possible to create a multi-site exhibit to engage science, art, and humanist communities.”

Big names from a burgeoning field

The exhibition brought together the work of leading bioartists—artists who work with live tissues, bacteria, and life processes in the same ways that other artists work with paint and canvas. To make their work, bioartists combine the scientific laboratory with the traditional artist’s studio. Several participating artists have founded innovative bioart labs at universities around the globe.

“The Libraries was a natural fit with its record of engaging exhibits, its understanding of the research life cycle, and its access to subject specialists and new technologies”

– Guest Curator Hannah Star Rogers

Art’s Work included artists who have exhibited widely and achieved international recognition, such as Suzanne Anker, Heather Dewey-Hagborg, Joe Davis, Richard Pell, Kirsten Stolle, Paul Vanouse, Adam Zaretsky, Jennifer Willet, Charlotte Jarvis, Maria McKinney, Emilia Tikka, Aaron Ellison, David Buckley Borden, Joel Ong, Emeka Ikebude, Kerasynth, Jonathan Davis, and Ciara Redmond.

Many of these artists have achieved acclaim in both the arts and the sciences. Jarvis’ work received a substantial grant from the Dutch government to pursue the creation of female sperm, which is referenced in her In Posse series in Art’s Work. The Kerasynth collective, which reimagines fashion through synthetically grown, biological textiles, was a finalist for the 2018 Biodesign Challenge at the Museum of Modern Art. Tikka, whose EUDAIMONIA film speculates about a future in which one can personalize one’s genome, was selected for the Bioartsociety’s Tokyo Art & Science Research Residency last year.

Renda captured this range of work in a 44-page, full-color catalog for Art’s Work, published by the Libraries and available through UNC Press. The beautifully designed book is a finalist for the Dedalus Foundation Exhibition Catalogue Award and contains essays from Art’s Work team members Roger Manley, the Gregg’s director, and Todd Kuiken of GES. An online version of the catalog is viewable on the Libraries’ website.

Margaret Atwood comes to campus

Writers don’t come any bigger than Margaret Atwood, and she is frequently described as our most important living author. In more than 50 novels, Atwood’s writing has proved as timeless as it is prophetic. Her most famous work, The Handmaid’s Tale—currently an Emmy-award winning Hulu television series—feels as relevant today as it was when it was published in 1985. Her long-awaited sequel, The Testaments, was an instant best-seller when it was published last year, garnering her a second Booker Prize.

And, on November 15, Atwood spent the day at NC State.

Atwood visited the Art’s Work exhibition at the Gregg—Rogers, Renda, and participating artist Suzanne Anker gave her a special tour—and had a group discussion with students and faculty. Then she gave a keynote speech to a sellout crowd at the Talley Student Union entitled “An Evening with Margaret Atwood: Literature to Explore Our Genetic Engineering Futures.”

Atwood has always possessed the uncanny ability to predict the future of technologies and society. Her 2003 book Oryx and Crake covers a host of issues including genetic manipulation, corporate domination, and global pandemics. One of Suzanne Anker’s contributions to the exhibition, in fact, references the novel. Sharing her thoughts on the intersections of technology and humanity, Atwood challenged the audience to think critically and engage with the world around them from different angles. But she also reminded them that they had agency in both the present and the future.

“As you know,” Atwood said to the crowd, “nothing is inevitable. There are too many variables.”

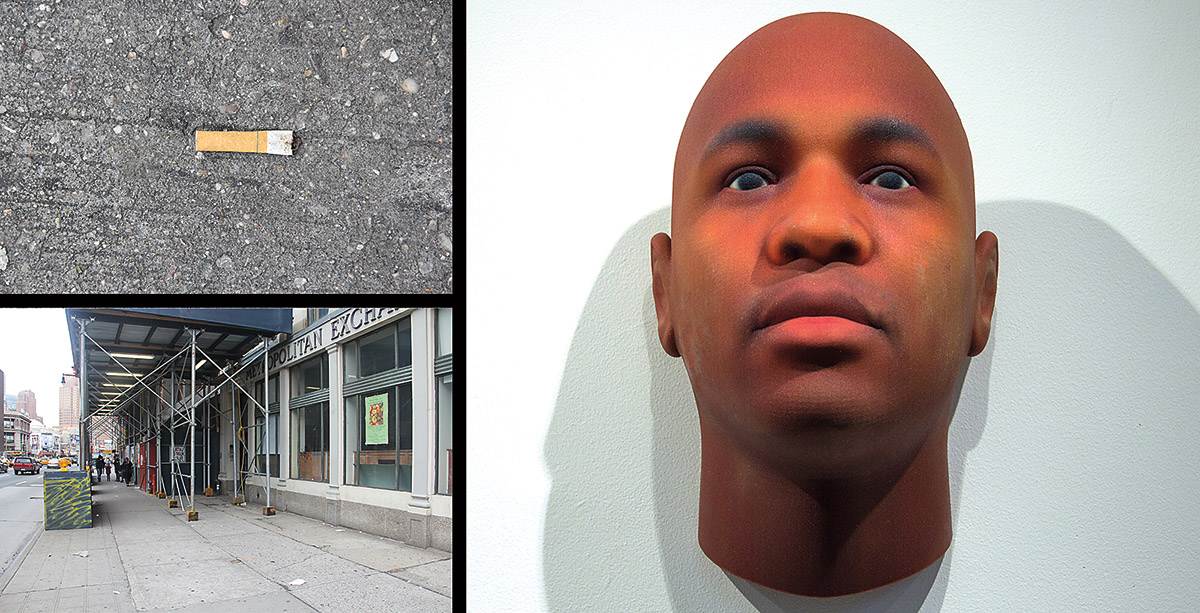

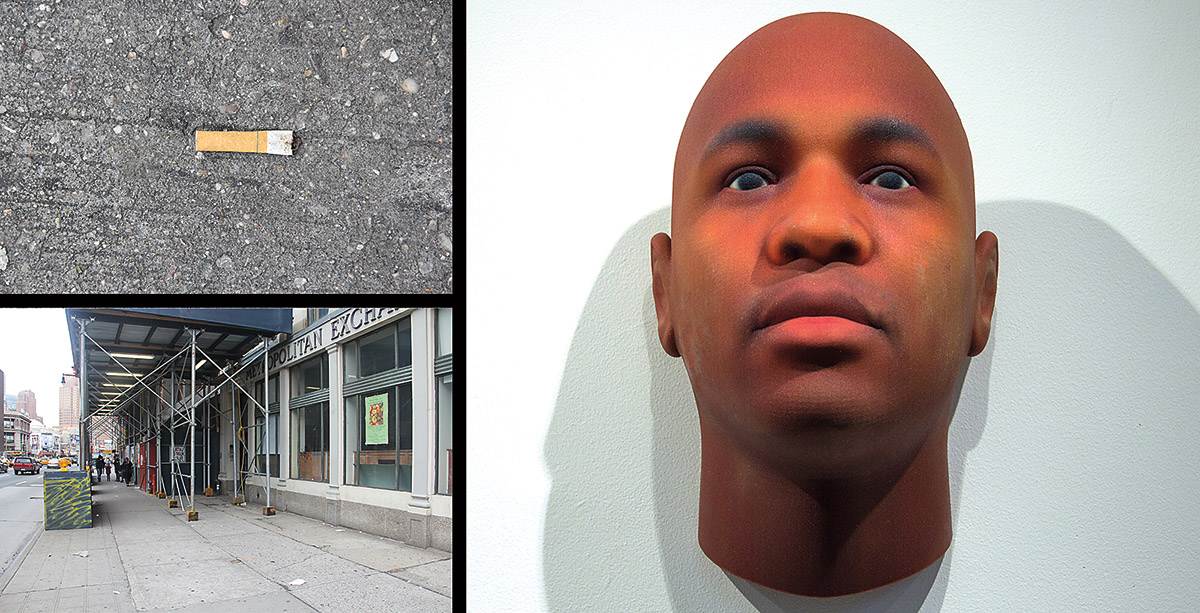

Many of the Art’s Work artists take contemporary innovations in the sciences as a starting point for speculation about possible futures, as Atwood does throughout her writing. In her Stranger Visions series of sculptural portraits, Heather Dewey-Hagborg collected hair, gum, and cigarette butts from New York streets and bathrooms, extracting DNA from follicles and saliva to computationally generate facial possibilities. In Ciara Redmond’s We Make Our Own Luck Here, the artist uses selective breeding to create clover plants with high incidences of four leaves, cheating the link between the rarity and luckiness of four-leaf clovers.

“I love Margaret Atwood’s goal of using literature to show people a dystopia that is really possible in order to get us to think more carefully about how we guide the use of genetic technologies,” Gould said in an NC State News article.

The Atwood event served as the Friends of the Library Fall Reception and was presented by the Friends of the Library and the Genetic Engineering and Society Center with support from the NC State University Libraries, the College of Humanities and Social Sciences, and the College of Sciences Spirit of Science Illumination Fund.

Corn maze or time machine?

Most exhibits directors hang artwork on gallery walls and place it in display cases. Renda traded her hammer for a shovel to plant and cultivate a quarter-acre corn maze instead.

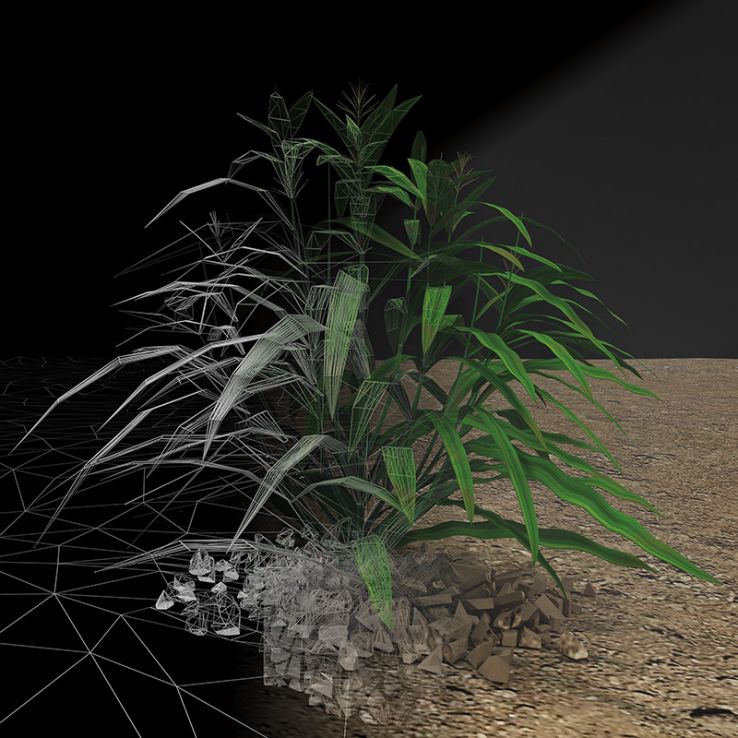

From Teosinte to Tomorrow was grown on the grounds of the NCMA’s Ann and Jim Goodnight Museum Park, in the shadow of a Vollis Simpson whirligig. Entering the maze’s twisting pathways represented a conceptual walk into agricultural history. At the center of the small stand of tropical field corn, visitors found an interior room with a raised bed of teosinte—the wild grass thought to be an ancestor of modern corn. Through countless harvests, the skinny, hard kernels of teosinte grass were gradually cultivated and hybridized into today’s juicy and sweet corn on the cob.

“That teosinte was in some sense genetically enhanced by subsistence farmers in Mexico since the time of the Aztecs,” Gould told IndyWeek. “Now we’re doing it in the laboratory with the same genes—so what’s the difference? Art’s work is to make us think and question.”

Renda and architect William Dodge’s design for the maze was inspired by photographs and drawings made by artist Josef Albers during the years he and Anni Albers traveled extensively in Mexico (1930s–60s). The Albers’ deep connection to Mesoamerican art, together with their importance to the growth of art and design in North Carolina, at Black Mountain College most notably, made these reflective works an apt source.

For the public opening of the corn maze in August, the Libraries teamed with Student Action with Farmworkers (SAF) for its annual End of Summer Celebration in the NCMA East Building. SAF hosted a reception and showed a documentary and theater program before attendees headed across the museum grounds to the corn maze. Museum representatives later said that the event was one of the most diverse programs the NCMA has ever hosted.

While the exhibition as a whole was open through mid-March, From Teosinte to Tomorrow closed at the end of October as winter approached. A virtual reality experience of the maze, however, was available at the Gregg for the duration of the exhibition.

Mice and spit?

Many Art’s Work artists visited during the opening week of the exhibition, and several did public projects on campus. Paul Vanouse, a bioart artist based in Buffalo, NY, collected people’s spit in the Talley Student Union Atrium for his “America Project.” Students and other visitors swished a saline solution and spit it into a common spittoon. Then Vanouse extracted the DNA from the combined spit samples and processed it as an undifferentiated whole to make iconic DNA fingerprint images of power—such as a crown and a flag—in video projections of electrophoresis gels in the exhibition.

Bioart legend Joe Davis brought a live mouse into the Hill Library’s Exhibit Gallery for his “Lucky Mice” work, which observes serendipitous behaviors to see if some mice are genetically luckier than others. Inside its cage, the mouse’s behavior—running on its wheel—operated a dice-throwing apparatus. The results of the dice rolls showed whether or not the mouse was lucky. Investigations of luck have been undertaken in psychology, cognitive science, information science and economics, but Davis pointed out that correlations of serendipity and genetics have never been studied. His use of live mice highlights human-animal relationships in art and science and examines protocols underlying use and care of laboratory animals.

Many exhibiting artists and campus scholars from both the sciences and humanities—including Art’s Work team member Elizabeth Pitts, an assistant professor at the University of Pittsburgh who received her doctorate from NC State and worked with GES—gathered at the Gregg Museum the day after the opening for a symposium that took the exhibition as a departure point for conversations about the future of biotechnology and genetics.

Years in the making

It takes time, and a lot of people, to plan a project of this scale and reach. Art’s Work really began back in 2016, with brainstorming by Renda and Gould, and their bringing Rogers into the project. Their work led to the exhibition’s first public showing in 2017, when Raleigh’s contemporary art museum, CAM Raleigh, hosted Shaping Our Genetic Future, a fun and provocative evening of interactive exhibits on April’s bustling First Friday art night. The North Carolina Science Festival also listed the event as part of its showcase opening.

Seven artists showed and talked about their work, and the improvisational acoustic band Cyanotype interpreted genetic structures and artists’ works as musical scores. Thousands of visitors handled extracted DNA, sniffed perfumes from extinct flower species, and peered through special glasses at large, 3D images of post-natural specimens.

The day after the event at CAM, 40 scientists, artists, humanities and design faculty, and museum professionals convened for a workshop at the Hunt Library to inform the exhibit’s curatorial team as they moved forward. The invited artists presented their work, Dr. Rob Dunn gave a brief history of biology and art, and Manley spoke about the Gregg’s collections. In breakout sessions, attendees discussed and shared ideas on the history of art and science, how to facilitate collaborations between disciplines, and to consider the possibilities and limitations of art engaging science. Notes and insights from the weekend contributed substantially to the curation of Art’s Work, providing Rogers with themes and questions to address in the exhibition.